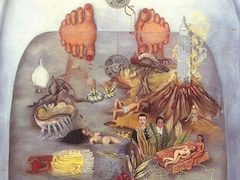

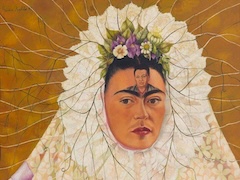

The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Myself, Diego and Señor Xólotl, 1949 by Frida Kahlo

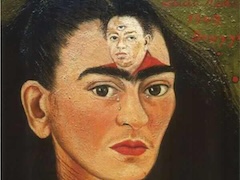

As the years went on, Frida took a more and more motherly role in relation to her husband Diego Rivera. He loved to be pampered, and she discovered that playing mother made it easier to indulge his mischief. Just as she could scold when he dropped his underwear on the floor or gobbled three scoops of pistachio ice cream, she could laugh at his sexual misadventures. She confided her maternal feelings to her journal: "At every moment he is my child, my child born every moment, diary, from myself." In her Portrait of Diego, written for the catalogue of Rivera's 1949 retrospective at Mexico City's Palace of Fine Arts, Frida said:

Women - among them I - always would want to hold him in their arms like a new-born baby."

That is exactly what she does in The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Diego, Me, and Senor Xolotl, 1949, a self-portrait that celebrates the final resolution of the Riveras' marriage. Here Frida is the earth mother/Madonna nurturing the baby she could never have - her "Dieguito." Now she does not need to clasp him tightly, for the couple's union is sustained by a series of love embraces that roots them in the Mexican earth and in the ancient dark/light duality of a pre-Columbian universe. Even Frida's itzcuintli dog, Xolotl, is encompassed by this vast interlocking pyramid of love.

Yet for all Frida's contentment in possessing her spouse, she knew, as she wrote in 1949, that "Diego has never been and never will be anyone's husband." Although she looks calm, tears still dot her cheeks, and a bright red crevasse cracks open her neck and chest. From it a magical fountain of milk sprays forth. In sympathy, the Mexican earth has a cracked breast from which one drop of milk appears. The baby Rivera holds an orange maguey plant, which looks like fire and might stand for what Frida called his "fountain-flower" (his penis), or it might stand for the fire of his genius, rooted in the Mexican soil. In "Portrait of Diego" Frida described the Diego she painted in her portrait. His bulging, wide-set eyes were, she said, "constructed especially for a painter of spaces and multitudes." The third eye opened in his forehead is the invisible eye of "Oriental wisdom," and his "Buddha-ish mouth" is set in "an ironic and tender smile. . . . Diego is an immense baby with an amiable face and a slightly sad glance . . . seeing him nude, you immediately think of a boy frog standing on his hind legs. His skin is greenish white like that of an aquatic animal.